"On Life and Math", Chapter 3: A Big Berkeley Ocean (Part 2 of 2)

It was at Berkeley, though, that my math-bestness began to slip. Some of the other kids were light-years ahead of me, speaking with enthusiastic expertise about fantastical-sounding topics that I’d never even heard of: quantum field theory, and noncommutative motives, and the geometric Langlands program, and on, and on, and on, and on.

How had I missed all of this? I’d been at the top… in my little Brown pond, at least. All of the super-advanced students seemed to be coming from Harvard, MIT, and Chicago. Unbeknownst to me, already in undergrad there had been a massive institution-based stratification underway.1 I began to feel resentful at my past self for not doing better in my undergrad applications.2

Sensing my slipping bestness, I subconsciously shifted my identity. Maybe it was just that I wasn’t a fast learner, or hadn’t yet been exposed to the best mathematics. I told myself: “You’d better work incredibly hard, if you want to have any chance at being truly good at math. You might turn out to be good or you might not, but if you don’t work incredibly hard then you’ve got no chance at all.”

This, this right here. This was the moment in which I abandoned myself. I felt like I was not good enough. At least not yet, and perhaps not ever. And that my only possible path to redemption was through the purifying self-punishment of intense work. I began to subconsciously deny my actual existence in favor of an idealized self-image. Said differently, I began to hate myself.3

I also found myself falling in love with a field of mathematics that almost nobody else at Berkeley studied: homotopy theory. I do think this was true love (and not just a defense mechanism), and indeed it began well before I even arrived at Berkeley. But it’s impossible not to notice that this was a field in which there was almost nobody else around to compare myself to.

In fact, there was just one other person doing homotopy theory at Berkeley: Eric.4 Eric started grad school the same year I did, but came in knowing a whole bunch more homotopy theory than I did — having spent an extra year after undergrad studying it under the supervision of Matt, a prominent figure in the field. We first met at a grad student welcome picnic. I remember telling him excitedly about Eilenberg—MacLane spaces and cohomology, and him responding by telling me excitedly about chromatic homotopy theory and the Adams—Novikov spectral sequence (see below). The latter topics are waaaaaaay more advanced than the former, but hearing him talk you wouldn’tve known it: Eric was so gentle and unassuming.

From that day forward, Eric took me under his wing — “dragged me up out of the mud”, as he once endearingly referred to it — and proceeded to spend sometimes as many as 15-20 hours each week getting me up to speed on homotopy theory. He’d meet with me for multiple hours straight, multiple times per week; and he’d write long, flowing, crystal-clear responses to my endless emails at all hours of the night. With our friend Cary at Stanford, we also organized the “xkcd group”: a joint student seminar where we gave talks about all the homotopy theory we were learning.5

This phenomenon — the massive effect that a community has on the goals and possibilities that people even think to envision for themselves — is articulated clearly in Paul Graham’s essay Cities and Ambition.

For instance, in certain San Francisco circles, it’s common to meet people who have founded their own companies, some of which are worth tens or hundreds of millions of dollars. As a result, people in and around these circles are more likely to even imagine that they might found a company in the first place. In most other places, this seems as outlandish as owning an emu farm.

In other words, the water we swim in dictates what we believe to be normal. (David Foster Wallace’s commencement speech This Is Water offers some dovetailing thoughts on how to live well, which were formative for me.)

I can scarcely fathom it, but when I was applying to colleges, I didn’t ask any of my math teachers for letters of recommendation. I feel ashamed to admit it, but I know the exact reason: it’s that I chose the popular teachers to write me letters — those of biology, Latin, and history. I was a solid student in those subjects, but nowhere near as exceptional as I was in math. But my calculus teacher was particularly unpopular, and so it somehow didn’t occur to me that she could nevertheless write me a good letter.

I actually only decided to apply to Brown at the last minute, and that required a letter from a math teacher since I was applying as an engineering major. I hastily and apologetically reached out to her, and she immediately submitted a letter for me with no complaints whatsoever about the 2-day turnaround (whereas it’s generally requested to give at least a month or two of lead time, ideally more). I’m fairly confident that she wrote me an absolutely stellar letter, and that that more than anything else is what got me in to Brown: I remember having a 108% grade in her class (including extra credit, which I always completed just for fun), far above all the other students — despite being two years younger than them.

To this day, I wonder how my life would’ve played out differently if I had had the sense to ask her for a letter of recommendation for all of my college applications, instead of just for Brown. I almost certainly would’ve ended up at some other, fancier college; but once there, it’s impossible to say whether I would’ve risen to the top, or simply slipped in math-bestness earlier in life. In any case, it’s clear that I would have eventually slipped, as evidenced by the existence of people like Terence Tao and Jacob Lurie. They’re truly a different species.

Nevertheless, from where I now stand, it’s mercifully difficult to really want things to have turned out differently, since I feel so grateful for all the experiences that have made me who I am today. But this gratitude is very hard-won, and achieving it has required first accepting many uncomfortable truths.

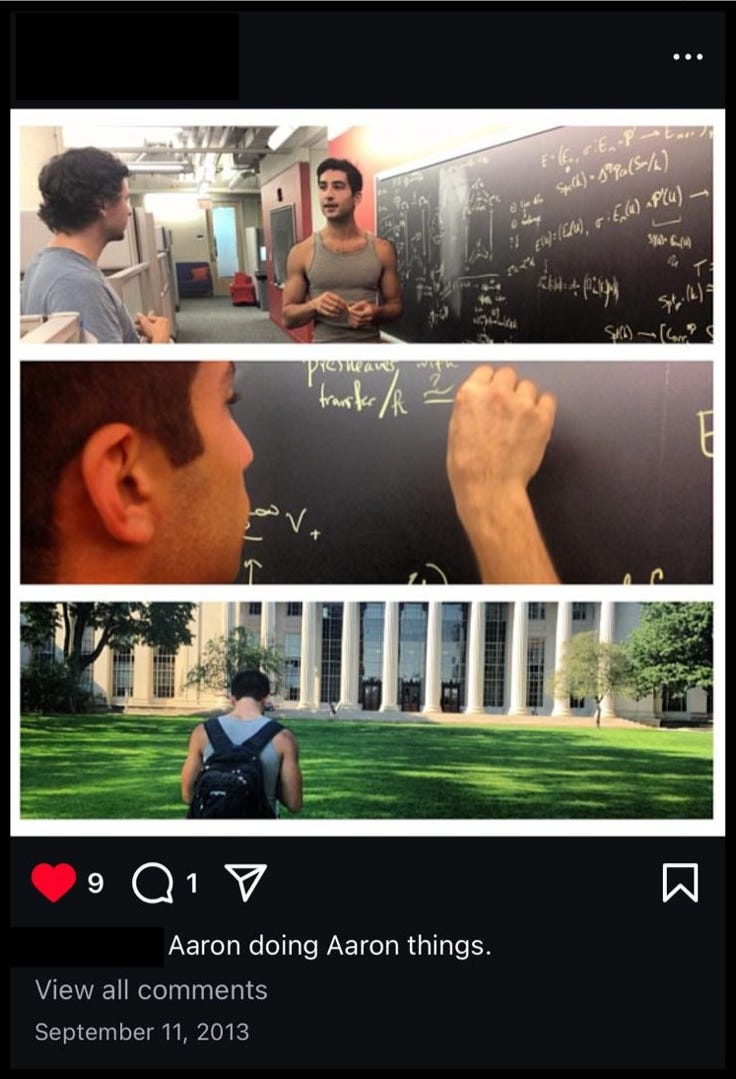

Another context in which I’ve noticed this same mechanism operating is physical fitness. At various times in my life I’ve been quite muscular (see below), and in particular have had seriously well-defined abs. Ever since I first reached that point, I’ve subconsciously considered that to be my “true” state, and have considered myself to be merely “temporarily embarrassed” when I’m not at that optimal level of muscle definition (analogous to the idea of America’s poor self-conceiving as “temporarily embarrassed millionaires”) — to the point that I still to this day sometimes find myself clenching my abs and sucking in my gut, even when I’m alone in a room with no upcoming interactions expected whatsoever.

This illustrates the problem with using self-hatred as a motivator: at best one feels like things are “as they should be”, but in literally all other cases — and there will be other cases — it causes a feedback loop of increasing self-hatred.

Other math friends sometimes jokingly referred to the two of us as “the Berkeley homotopy theory department”.

The “Xtraordinary cohomology theory & K-theory Collective Discussion group”: making xkcd not stand for nothing since 2010!